Laboratories of Living

Navigating the New Digital Chasm

This morning, I saw a Tweet (err, X Post) from

sharing that perspective that LLMs pose a challenge to the core structure of colleges and universities:But it's not just LLMs. And not just colleges and universities.

We're living through a paradigm shift in the definition of what it means to be human. As a culture, we are aggressively shifting from a focus on the written word back to the oral tradition. It started with rise of TVs in mid-twentieth century, expanded to the emergence of mobile phones in the early 21st, and then the constant deluge of streaming video through those phones. And now, we can even strike up a conversation with an artificial intelligence at any time, on any topic.

Much of our post-Enlightenment modern world depends on the historical shift from oral forms of transmitting and consuming information, to literacy as the chief means of cultural expression. Just this morning,

(Dr Colin Lewis) wrote a relevant post about Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death.Lewis notes:

Our modes of communication, once based on written prose with its demands for attention, reflection, and rational thought, have been reduced to 280-character sound bites, each begging for instant emotional reaction rather than patient contemplation. The decline in public discourse that Postman spoke of is now an outright nosedive, accelerated by algorithms that feed us morsels designed to inflame rather than inform.

McCluhan's famous “the medium is the message” doesn’t go far enough: the medium refines the messenger (and messengee). In Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, Walter J. Ong explored the influence of oral and literate traditions. “Oral communication unites people in groups,” Ong writes. “Writing and reading are solitary activities that throw the psyche back on itself.” Beyond encouraging interiority, writing converts lived experiences into concepts. “Writing fosters abstractions that disengage knowledge from the arena where human beings struggle with one another”, Ong writes. “It separates the knower from the known. By keeping knowledge embedded in the human lifeworld, orality situates knowledge within a context of struggle.”

I'm not going to recap Ong's whole book. The point here is that a shift from a literary means of encoding and sharing information, to an oral one, has some pretty fundamental repercussions on our individual psyches, and how we related to each other.

In his Substack,

recently posted about the general vibes of the Internet, and our culture. “Why does it feel like we’ve been swept away by some invisible current, carried so far from where we started that we can no longer see the shore?” Walters asks. He attributes the cultural hangover not just to “enshittification” of online content, but the long tail of internet culture. He writes: “So many people I know talk about feeling unmoored, like the shared values that anchored us were cut loose and sank before we could catch them.”But is it possible that our increasingly polarized and “tribal” landscape isn’t the result of social media Balkanization, but rather, a byproduct of the core shift in how we communicate to visual and oral forms?

I experienced a very specific aspect of this shift when I worked at Loom, the video messaging startup. We used Looms for everything – it's always good to dogfood your own product. And as a remote and distributed company, Looms were (and are) a fantastic tool for sharing context with team members and getting on the same page. But we also found that the reliance on Looms could limit analytical thinking. Several Loommates reported that they had lost the muscle of writing longer-form memos and thinking critically.

In his most recent roundup post,

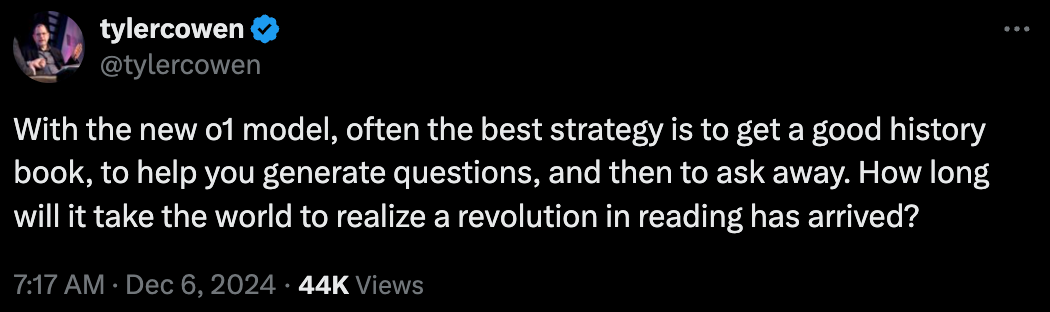

pointed to an article from The Atlantic on the state of literacy in today's college students. “Many students no longer arrive at college—even at highly selective, elite colleges—prepared to read books,” Rose Horowitch observes. This observation isn't just the usual “kids don't do the reading” – it’s that they’re fairly incapable of doing the reading at all. The article points to many causes, ranging from the environmental (smart phones) to pedagogical (a shift away from teaching full books to reviewing selected snippets). One particularly damning observation is that students view reading as a relic of the past. Horowith writes: “A couple of professors told me that their students see reading books as akin to listening to vinyl records—something that a small subculture may still enjoy, but that’s mostly a relic of an earlier time.”And putting aside the capability of reading, the how of reading is radically changing with the rise of LLMs. No one can question the intellectual bone fides of Dr Tyler Cowen of Marginal Revolution. He notes on X how AI radically changes how we consume books:

Likewise, Every founder

has shared that he reads with ChatGPT's realtime voice interface enabled next to him, so that he can always ask a question to explore context of whatever work with which he's grappling.It's too easy to point at LLMs and say “AI bad for learning". Cowen and Shipper show it's not so simple – used well, AI can provide an incredible tool for deeper engagement.

In his Substack on Postman, Dr Lewis writes:

In the end, the question is not whether social media makes us better or worse. The real question is: Are we willing to confront the ways in which our habits and choices shape us, and are we prepared to reclaim our agency in an age of constant distraction? Postman’s work challenges us to do exactly that, reminding us that the medium matters, but our response to it matters even more.

Similarly, Dr

wrote this week to provide a framing for how we evaluate the impact of technology, shifting from a focus only on harms, to one that also incorporates a perspective on human flourishing. “If we are to make lasting progress in understanding the ethical contours of our pursuits”, Brake writes, “we must see not only the potential harms of a given endeavor, but even more importantly the sort of vision of flourishing embedded within it.”But this is a very big ask of humanity. I’m all about exploring the implications of technology on our virtue, but simply considering this question is a luxury good. If everyone needs to be assessing the role of their technology diet on their virtues, I think we're going to face a tough road. Most everyone knows the dangers of salt and fat to health, but nutritional education hasn’t resulted in a world of super-fit citizens. When the default option isn’t just the default, but is addictive, it’s hard to make the “better” choice.

I can’t help but sense that the “digital divide” is expanding into a “digital chasm", or perhaps even more than that, a bifurcation in the very nature of reality. The original digital divide delineated those with and without access to the internet. Now, the digital divide may be one that separates those who use AI to help them think, and those who fall into a pattern of pure consumption.

In this world, centers of learning can break down the digital chasm, providing not just an ability to virtuously leverage technology, but to inspire the desire to do so in the first place. Intrinsic motivation towards intellectual pursuits matters now more than ever, when the very basics of literacy are increasingly “opt-in".

Which brings me to the most influential piece I read this week, an essay from

from October, which was itself an update from a 2021 post. Sarris is a technologist who, like me, has adopted a rural life in New England, and frequently shares eloquent perspectives on the intersection of human flourishing and technology.The whole post is worth reading. There's a number of points that made me stop in my tracks as I read them. One breathtaking quote reminded me of the vast array of human batteries in The Matrix:

We have a public imagination that cannot conceive of what exactly to do with children, especially smart children. We fail to properly respect them through adolescence, so we have engineered them to be in storage, and so they shuffle through a decade of busywork. Partly, the length of schooling has increased simply because it could—because we no longer need children to work, yet need them to do something while the adults go do theirs.

The modern challenge to the educational system isn’t just a matter of LLMs and colleges. It’s about how we empower children to find what they care about, and how we provide them the skills to pursue whatever they find. Sarris writes: “We should be thinking much harder about ensuring children can make meaningful contributions, and we should teach them in ways that are sensitive to the context of the real world.”

What does this new system look like? There’s no clear answer, and certainly not a migration plan. But Sarris argues that we shouldn't wait around. “[W]aiting for any kind of policy daydream is a mistake,” he writes. “If a system lacks imagination, it is best to supply our own. History ebbs and flows with opportunity, and we find ourselves at a fortunate time.”

Sarris is right that those of us with the privilege to explore new options should be doing so. And even for those from privilege – perhaps especially for those from privilege – choosing the alternative path is not easy. The system expects you to stay on its rails. But the rails are obviously coming apart.

I wish I could end this roundup with a link to some brilliant Substack essay that points the way forward. I certainly haven't found one. But one thing I have seen on Substack is the number and breadth of people who are wrestling with these questions. From academics like Dr Robbins, Dr Brake, and Dr Lewis, to curious intellectual entrepreneurs like Zohar Atkins, to deep thinkers and parents like Sarris, there’s no end to the number of experiments with new ways of learning and living.

US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously described each of the United States as “laboratories of democracy", stress testing different blueprints to virtuous government. In many ways, the Internet (and Substack in particular) provides us with “laboratories of living": explorations of how to enable flourishing as we face the wealth of challenges and opportunities ahead of us. We are not experimenting alone. We are joining together, crossing boundaries as never before, to find and define the bridge that will take all of us into our new age – whatever comes next.