I'm nearly eight months into leaving Loom to start my own company. And I use the term "my own" loosely: I'm working with three amazing co-founders, former friends and colleagues from Airbnb. My "own" journey is really an "our" journey.

The first two months of that journey was evaluative, rapidly exploring possible ideas as a child appraises unfamiliar toys, excitedly picking one up as if it's the greatest thing in the world before dismissively tossing it aside and picking up another. And even before leaving Loom, my mind had been spinning for months, trying to find "the right thing".

Since going "all in" on a direction, several people have asked me how I "knew" the right direction to go. How did I shift out of evaluation mode and into a single space to pursue?

I didn't "know". You can't "know".

If the thing that's holding you back from starting a company is choosing the right thing, I have good news for you: there is no right thing.

Starting a company is obviously a major commitment. In her own reflections on her startup journey, Dani Grant at Jam summarizes why you should expect to be making a ten year bet:

...starting a company is embarking on a decade+ long journey. That the idea you choose to start a company about is going to completely shape who you’ll spend time with, how you’ll spend your time, who you’ll meet, and what you’ll talk about at every customer meeting, recruiting event, even at house parties, family get togethers, etc – for a decade+

She goes on to describe the kinds of questions to ask yourself before committing to any idea. And Dani's right: chasing a unicorn is as ill-advised in startups as it is in fantasy land. A little due diligence before giving up a reliable income and committing to a concept, let alone a team of other humans, is an absolute requirement. If you don't ask yourself the tough questions, then investors and customers will, and you don't want to be reasoning out answers in real time.

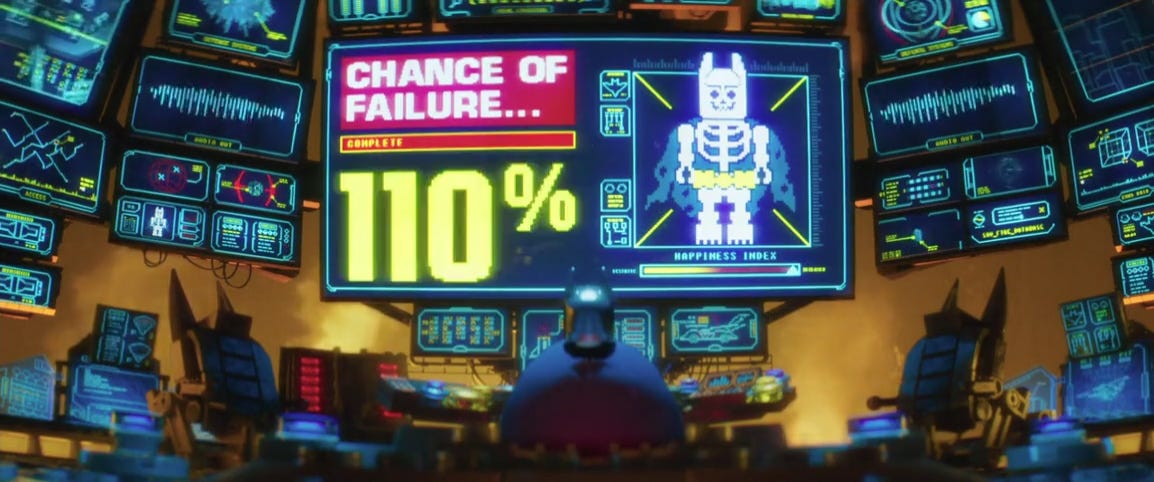

But for all the folks who throw themselves on a hype idea without much reflection, I think the larger (and silent) failure mode of any startup is analysis paralysis. Should I start a company? What should I start? Is this the right idea?

"It's the right idea" is the wrong question. There is no right idea.

You simply do not have the information necessary when starting a company to make a "sound" decision, for the same reason that VCs bet on people more than anything at pre-seed stages. There's no data to rely on, just feels and vibes.

Is the problem I'm solving worth paying for? Is my solution blocked by another problem I don't know about? Is there an incumbent building to solve my idea right now? Is there a hyper-capitalized peer startup about to emerge from stealth with a killer solution? Will I hate my co-founders in six months? Will they hate me? Will the macroeconomic conditions completely change and alter the basic assumptions underlying the company?

You have zero agency in answering these questions. You simply cannot predict the future. The answers will be provided by the universe: not you.

But there is a very important question for which you do have agency. Not "is this the right idea?" but "is this the right commitment?" And commitment is open-ended, because you might not be committing to an idea at all: you might be committing to co-founders. "I don't know if this idea is the right one, but we'll figure it out". You might be committing to a problem, a population of customers, a mission.

There are few guarantees in startups, but one certainty is that you will get things wrong. And that could include your initial idea, or solution definition, or ideal customer, or any number of other foundational assumptions. And you will continue to get things wrong, over and over again.

Deep research into foundational questions will only give you false hope of avoiding failure. As the saying goes, "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth". You can't truly learn until you're in the proverbial arena. You can't see the future until you get there. And odds are your venture, when judged as a business, will fail.

“Is this the right idea?” is what I call a “universe decision”. How do you evaluate “right”? And can you truthfully control the outcomes to ensure that “rightness”? On the opposite end of the spectrum from a "universe" decision is a "me" decision, one in which you have agency. And, well, the boundaries of a "me" decision are pretty narrow. As the Stoics say, you control how you shoot the arrow, not where the arrow flies.

Like every New Englander I grew up hearing Robert Frost's "The Road not Taken", and have been re-acquainted with it in recent years thanks to Vivian Mineker’s beautiful illustrations. Frost concludes:

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

But there's an alternate narrator who could conclude: "I took the [road] more traveled by, / And that has made all the difference", and it'd be no less true.

Our lives and decisions have meaning by our active choosing. Not in our current perception of the rightness or wrongness of choices we've made in the past. Every day when we wake up, we choose again, who will we be, what we will do, how we will orient ourselves. Every moment, every breath, we have the opportunity to choose and choose and choose again.

The choosing makes the difference.

So don't fret about the "rightness" of your choice. Focus on your choosing.

Do I seek the advice of mentors and friends who have lessons to share? Do I listen to them with an open mind?

Do I pause to evaluate an idea with critical thought, instead of jumping at the latest fantasy?

Do I balance my rational analysis with an trusting awareness of my gut and heart?

Do I observe myself, ask questions of myself, and grow from the answers?

Do I remain open to the truth that my life is outside of my control?

These are the inputs to good choosing.

From good choosing comes choices. Whether those choices are "good" or "bad"... well, even that evaluation is a choice.

So stop worrying. Start choosing. And then choose again.